I camalli

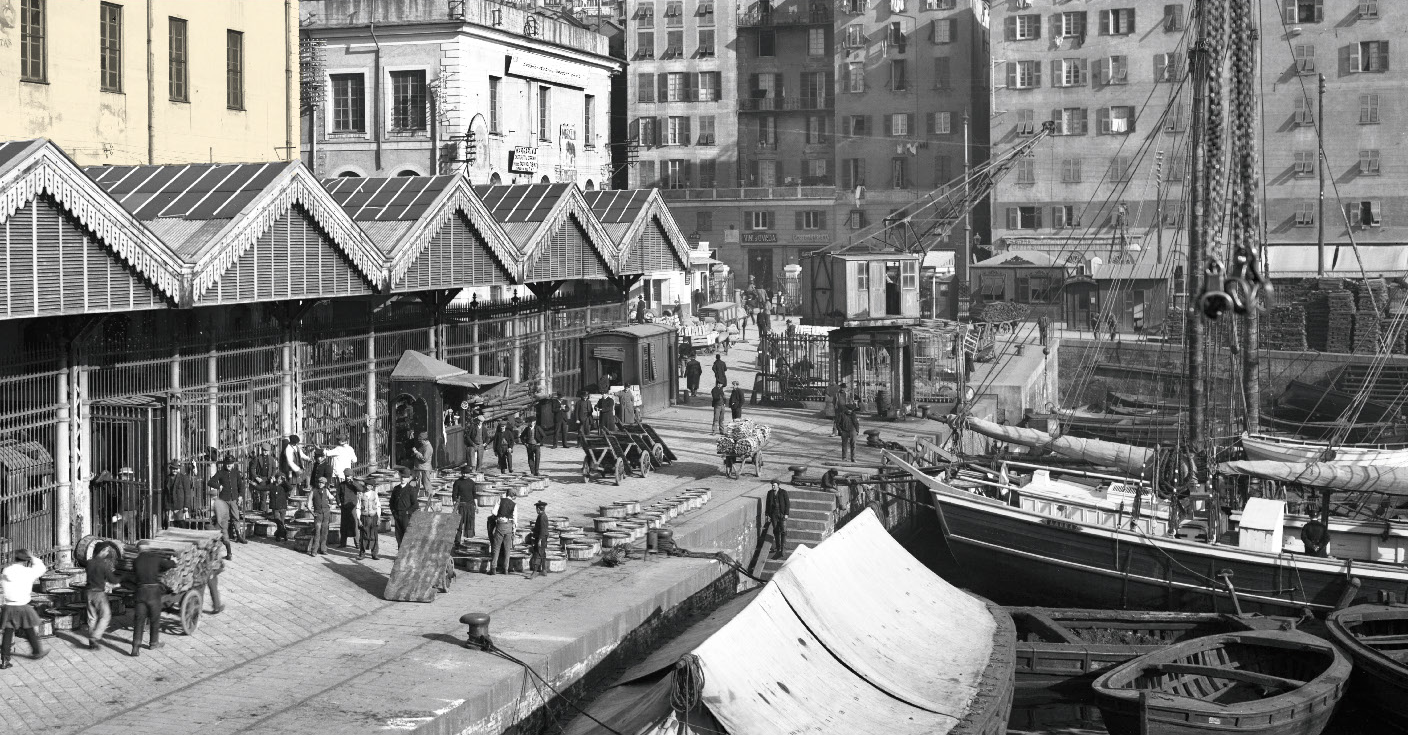

L’antica darsena di Genova a inizi Novecento. L’edificio che si intravede sulla sinistra (beige) è parte oggi del Galata Museo del Mare. La struttura in ferro e vetro prospicente, invece, non esiste più. In questi magazzini si stoccavano formaggi, olive, stoccafisso, pesci salati, che qui giungevano su chiatte o su vagoni ferroviari. Sulla banchina i camalli con i tipici carretti // The old dock of Genoa in the early 20th century. The building on the left (in beige) is now part of the Galata Maritime Museum. The iron and glass structure in front, however, no longer exists. Cheese, olives, stockfish and salted fish were stored in these warehouses and brought here by barge or rail. On the quayside the Camalli with their typical carts

Quando si dice ‘camallare’ per dire ‘portare con fatica’

Per secoli, mentre le operazioni di carico, scarico e stoccaggio delle merci destinate al Portofranco (parte del porto libera da dazi) era di competenza della Compagnia dei Caravana, sotto il diretto controllo della Casa di San Giorgio (una sorta di autorità portuale ante litteram), la gestione degli altri traffici era in mano a vari gruppi di facchini diversamente organizzati. Questi venivano genericamente chiamati camalli (il termine ‘hamal’ in arabo indica proprio questo mestiere) e si differenziavano al loro interno per le merci che movimentano (olio, vino, carbone, grano e farine) o per la zona in cui operavano. Anche dal punto di vista abitativo tendevano a insediarsi in città secondo ambiti merceologici. La loro maggiore diffusione avvenne nella seconda metà del Settecento in parallelo allo sviluppo fiorente dei commerci con l’America.

A fine Ottocento la crescente domanda di carbone aumenta ulteriormente la richiesta di camalli per sveltire le operazioni portuali soprattutto in relazione allo sviluppo della ferrovia e, in seguito, delle strade camionali.

The Camalli

In a time when ‘camallare’ meant ‘to carry with effort’

For centuries, while the loading, unloading and storage of goods destined to the Free port (the duty-free part of the port) were handled by the Caravana Company, directly controlled by the House of St George (an ante litteram port authority), the handling of other cargo was managed by various groups of porters. These were generically called ‘camalli’ (the term ‘hamal’ in Arabic refers precisely to this trade) who were divided according to the goods handled (oil, wine, coal, wheat and flour) and the area of operation. They lived in different neighbourhoods according to the type of cargo they handled. They became more numerous in the late 18th century as trade with America flourished.

At the end of the 19th century, the growing demand for coal further increased the demand for ‘camalli’ to speed up port operations, especially in conjunction with the development of the railway and, later, of truck roads.